Saudi Arabia’s debt surge: Cementing reliance on international funding

The increasing liquidity squeeze in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s (KSA) financial system has been causing heightened levels of debate for some time. A growing economy and the financial demands of the mega-projects that are under way are hoovering up cash faster than the domestic system can supply it. For context, recent reports suggest that the new city of NEOM could cost $8.8tn to build, which is around 25 times KSA’s annual budget.

Until recently, the Saudi business complex was able to meet its financial needs by raising money locally, generally via bank loans or by issuing sukuks into the strong domestic investor base (often private banks managing the wealth of high-net-worth individuals). However, the system has become too stretched. Credit growth has outstripped deposit growth for several years, while local investors buying financial assets must withdraw money from their bank accounts to do so, meaning that financial investments cause a reduction in banks’ deposit funding as local funding is cannibalised.

On top of that, deliberate oil production cuts and weaker oil prices have reduced oil revenues from SAR 857bn in 2022 to a projected SAR 608bn in 2025, contributing to a swing in the national budget from a surplus of 2.2% of GDP to a projected deficit of 4% over the period (using IMF numbers). The deliberate attempt to diversify away from oil therefore comes at a budgetary cost, at least for now, meaning that the country needs to attract more external funding.

If domestic liquidity is challenged, the logical step for a highly-rated country to take is to seek funding from abroad, which is precisely what has occurred. International debt issued by KSA and its large banks/corporates has surged in recent years. KSA sovereign and quasi-sovereign issuances now account for 5.1% of the most widely used EM sovereign bond index (JPM EMBI), meaning that it is now the largest issuer in that index. Its corporates now account for 4.3% of the corporate version of that index (JPM CEMBI), in which it has become the fourth-largest constituent. That represents a stunning change in its international market presence.

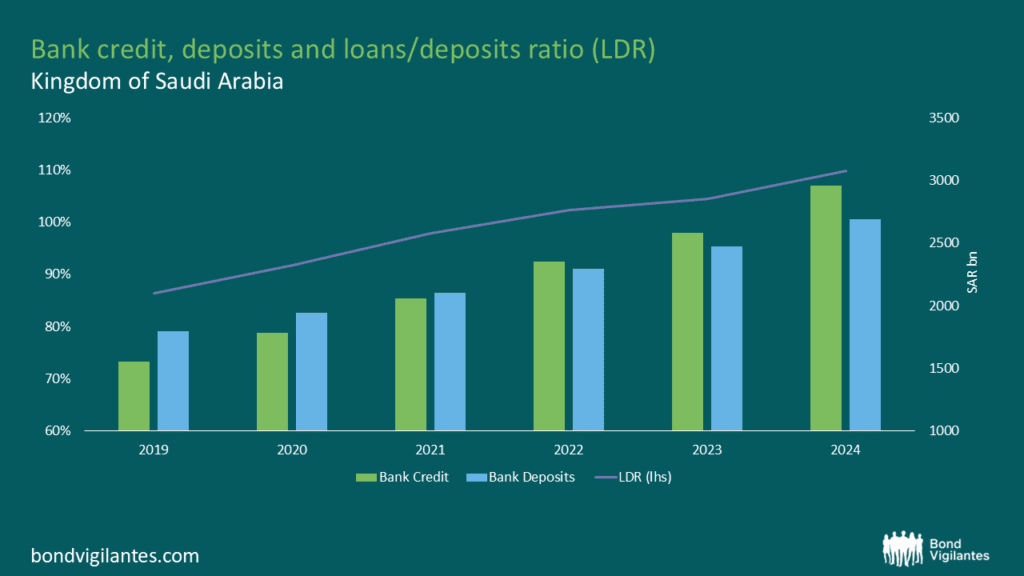

A glance at financial sector balance sheets shows that the need for international funding is structural – it is here to stay. Overall bank loans have grown at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 14% since 2019, with deposits growing by just 8% over the same period. In cash terms, loans have doubled from SAR 1.5tn in 2019 to SAR 3.0tn as at end-2024, while deposits have increased much less, from SAR 1.8tn to SAR 2.7tn. In 2019, therefore, the financial system had more than enough deposits to fund the economy’s credit needs; by 2024, this is patently no longer the case. In fact, the system’s loans/deposits ratio has weakened from 86% to 110% over the period. The conclusion is simple: banks are now dependent on wholesale funding if the current rate of credit growth is to be maintained.

Source: SAMA

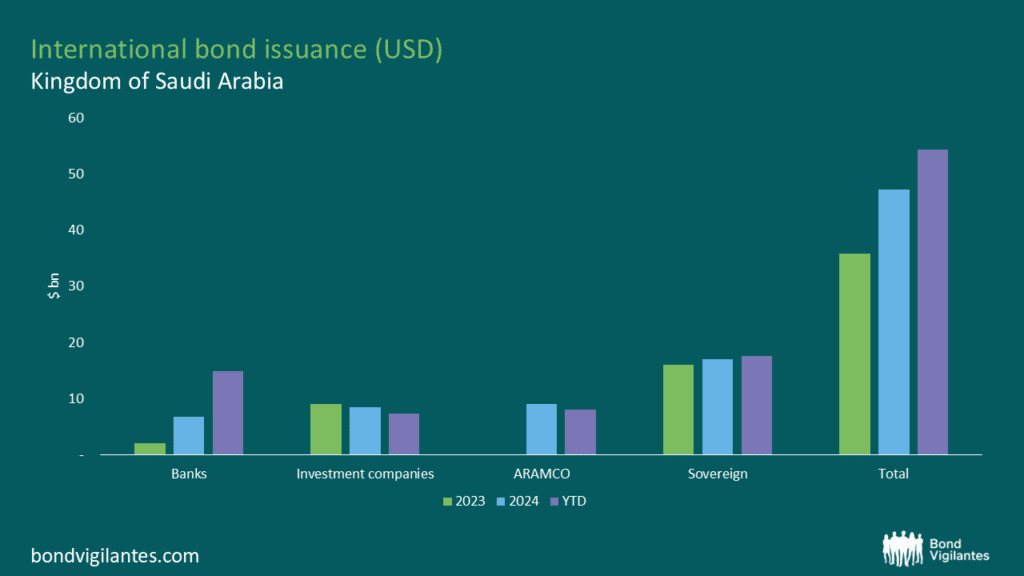

We can see the scale of the change in issuance of international bonds, which has soared in the past few years. In 2023, KSA banks issued $2.0bn of bonds, accounting for around 6% of total issuance from the Saudi complex. In 2024, this grew to $6.8bn (14% of total), while so far this year banks have already issued $14.9bn of bonds, comprising 27.4% of all Saudi issuance. And it’s not just the banks that are issuing more debt internationally. KSA’s funding needs mean that it is issuing through every vehicle at its disposal, including cash-rich Aramco and its sovereign wealth fund (PIF). Total Saudi debt issuance ballooned from $36bn in 2023, equating to around $3bn per month, to $54bn year-to-date or around $6.4bn per month.

Source: Bloomberg

It is very clear where all this leads: the KSA complex is structurally increasing its reliance on international debt markets. Banks are taking an ever-greater share of Saudi issuance, which also seems to be a persistent trend. KSA is therefore increasingly dependent on international investment to fund its domestic priorities, while the abundance of supply and the prevalence of more price-sensitive foreign investors in its investor base means that Saudi bonds may struggle to perform for a while. We wrote previously that the technicals of the sukuk market would generally assure tight spreads and strong performance (see here). The times, they are a-changin’ – that model no longer applies.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.