French government should push for further tax and labour market reforms

France has a unique social model. It originates from the end of the Second World War, when the National Council of the Resistance (NCR) hastily put together a plan to rebuild the country after five years of Nazi occupation. Despite not having any official political affiliations, the NCR was in fact influenced by left wing individuals and the “National Front”, a communist party. The NCR’s “action plan” helped shape France in the aftermath of the war and is one of the reasons today that trade unions have such a prominent position in society and why the French are so fond of their “established social rights”.

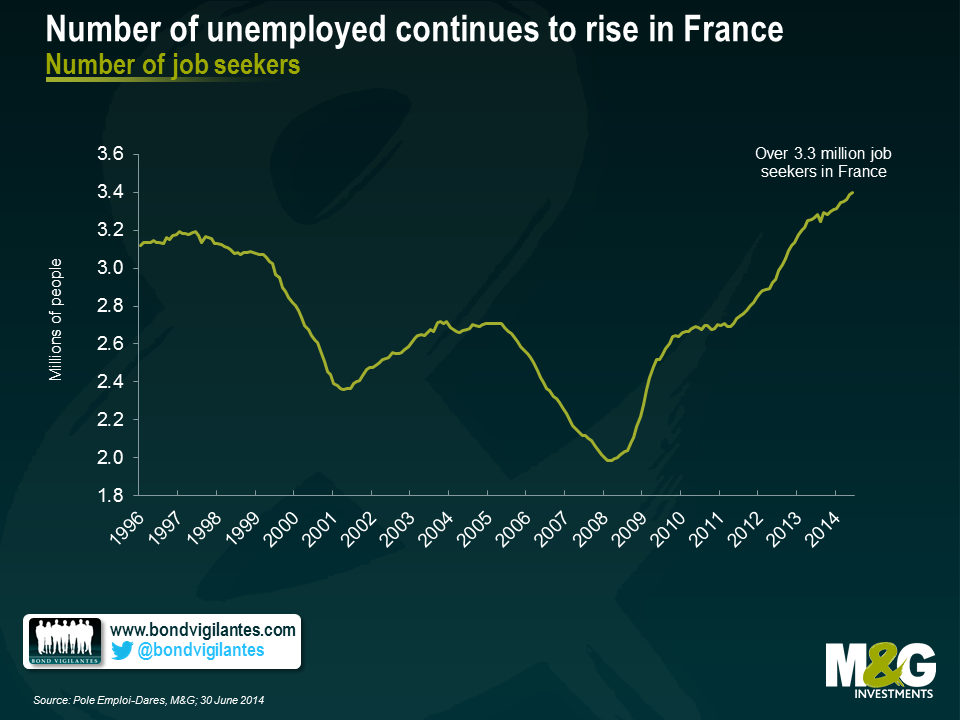

Since then, reforming France has always been a difficult task. Given that it was announced last week that the country has experienced a second consecutive quarter of no growth, it seems obvious that some sort of change is urgently required. France has grown by only 0.1% in the past year. Despite extremely low interest rates and fiscal tightening, the government’s budget remains in structural deficit and the debt to GDP ratio has increased from 77% to 93%. More worryingly, despite French President Hollande’s very vocal claim that he would “invert the unemployment curve” by the end of 2013, the number of job seekers continues to rise at an alarming rate, hampering consumer confidence and business spending.

So what can the Hollande government do in a country that is difficult to reform and where scope for public spending is limited?

First of all he should aim to simplify France’s highly complex tax regime, which over the years has become almost illegible. This toing-and-froing over taxes continues to hurt the French economy by creating uncertainty and hampering business investment. In the last 2 years alone, French legislators have created 84 new taxes, for a total of €60 billion Euros.

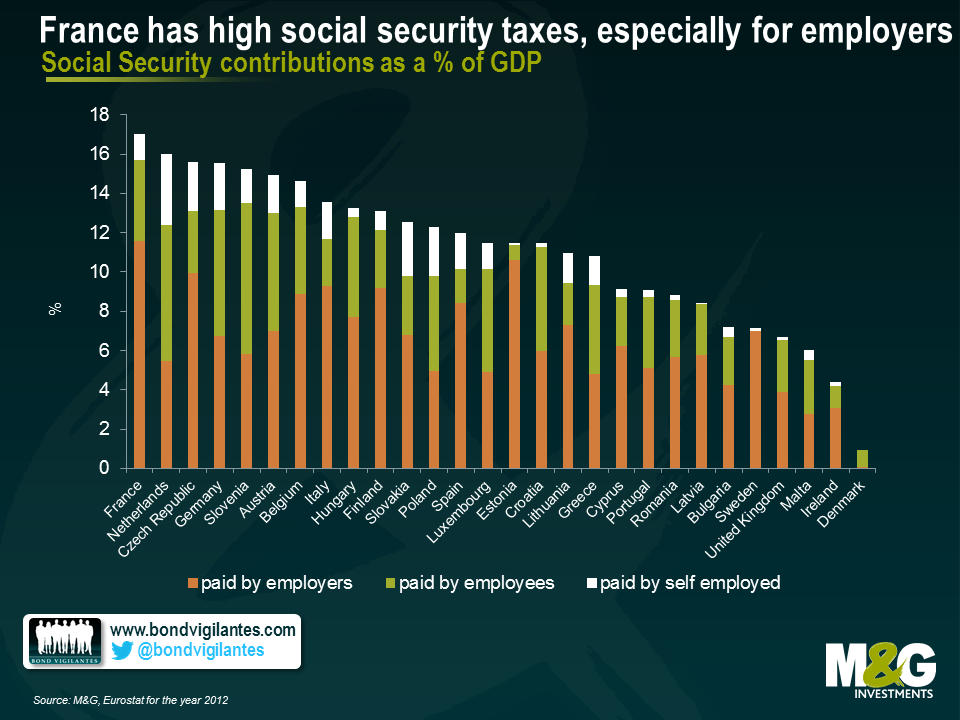

Second, the government must reduce the burden of social security contributions on the business sector. Today, France spends 17% of its GDP in social contribution taxes, the highest amount out of all of the 28 EU countries. While many people in the country believe that this is the price to pay to finance France’s generous welfare system, its financing relies too heavily on businesses. In the rest of Europe the burden of social security payments is shared on average equally between employers and employees. In France, almost 70% of these payments are paid by employers. This has a direct effect on the cost of labour and diminishes companies’ abilities to compete in an increasingly globalised world. The French government has started to address this issue by granting a €20 billion tax credit (CICE) to all French businesses, but much more needs to be accomplished. Indeed, in order to put France on equal footing with its neighbour Germany, employer social security contributions would need to be reduced by a further €80 billion per year.

Finally, the government should also tackle the excessive bureaucracy in the labour market. For example, many small firms today refuse to grow beyond the threshold of 50 employees because exceeding this number triggers a raft of regulatory and legal obligations. It would make sense to push this threshold to 250 employees, and bring France in line with the European norm. The French Labour Code is 3500 pages long and weighs 1.5 kilo, while the Swiss Code, where unemployment is 3% rate, is 130 pages and weighs 150 grams (anecdotally comparing unemployment rates with the number of pages of labour codes for different countries could be the subject of a future blog). This excessive bureaucracy is partially the reason why France’s competitiveness has been declining in recent years. In its latest Global Competitiveness report, the World Economic Forum ranked France 23rd overall, but 21st in 2013 and 18th in 2012. More alarmingly, the country is ranked 116th for “labour market efficiency” (out of a total of 148 countries), 135th for “cooperation in Labour-employer relations” and 144th in “hiring and firing practices”. When asked what the most problematic factor for doing business in the country, the number 1 answer provided by respondents was “restrictive labour regulations”.

As France teeters on the brink of recession, Hollande is today in a very difficult position. A complete overhaul of the French social model would create much civil unrest and probably push the country into recession. On the other hand, doing nothing is likely to have the same effect as France would continue to lose competitiveness on a global scale. In a recent study published by “Le Monde”, 60% of respondents said they were “satisfied” with the French social model, but 64% also declared that the model should be at least partially reformed. The French government should use this as a sign that it can make some adjustments to the French tax system and labour markets, without jeopardising its chance of being re-elected in two years. With its popularity at an all-time low and unemployment at an all-time high, there is no more time to waste.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

17 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox