Watching the news flow on the global economy is dispiriting. Ask an economist what springs to mind when they hear the word “Europe”. They will probably reply with thoughts about negative interest rates, deflation and debt concerns. It isn’t much better when you bring up the economic outlook for the US (“the upcoming election is a concern”), Japan (“the BoJ is at the limits of monetary policy”), UK (“business and consumer confidence will be hit by Brexit”) or China (“the banking system could implode”). It seems that there is little reason to have a positive outlook at this point in the cycle.

Being bearish is hard wired into human psyche. It is the reason newspapers lead with alarmist headlines. Indeed, living memory is littered with apocalyptic predictions including nuclear war, airborne viruses and the millennium bug. The fact that these predictions did not materialise does not mean that current concerns are unfounded. However, there are reasons to be optimistic about the future for the global economy, despite the current doom and gloom.

The world is more connected than ever before. The internet is changing the ways that people work, create, and share ideas. Importantly, it is estimated that 46% of the world’s population now have access to the internet at home, which is up from only 6.8% in 2000. Around 3.4 billion people are expected to be online by 2017.

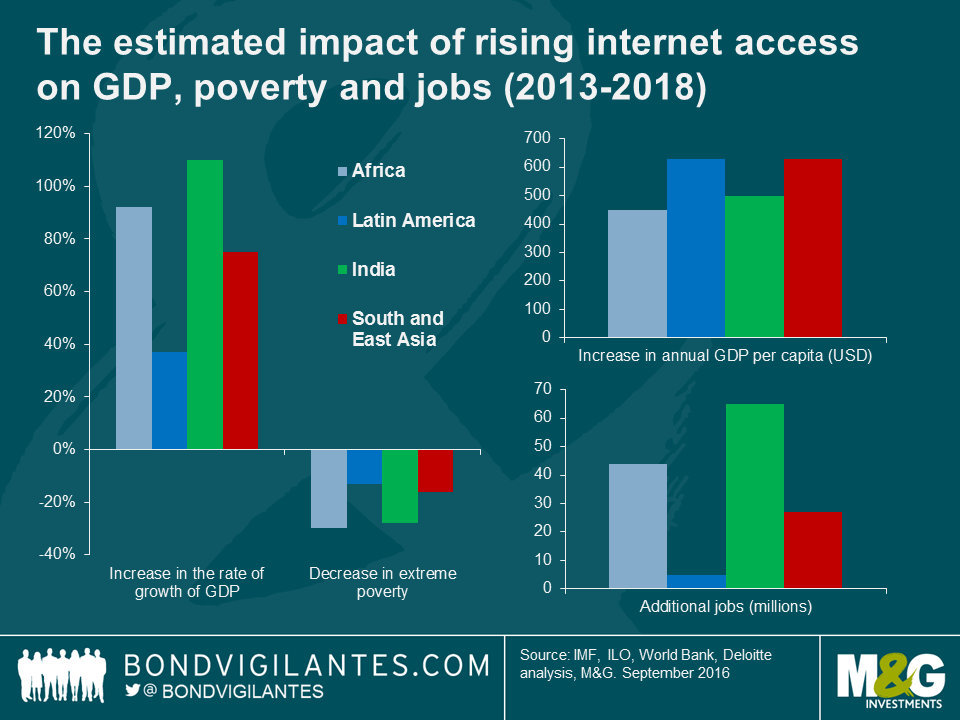

Rising internet access is important in that it enables economic growth in both developed and developing economies. The internet facilitates information flows, innovation, financial capital access, entrepreneurship and labour enhancement. The end result is greater productivity levels for labour and more efficient use of capital. In a report entitled the Value of Connectivity, Deloitte estimated that greater internet access in the developing world could result in an additional $2.2 trillion of additional GDP (the equivalent of Italy’s economy) and more than 140 million new jobs (which is almost the entire population of Russia).

The increase in internet access can also play an important role in reducing extreme poverty. The World Bank estimates that the number of people living in extreme poverty (under $1.90 a day) around the world fell under 10 percent of the global population in 2015. Poverty rates have reduced significantly over the past 35 years, coinciding with the benefits of greater internet access in the developing world. With a superior demographic profile and rising lower and middle class wealth, the developing nations have the ability to generate superior economic growth rates over the long term.

The internet has also led to the rise of the ultra-wealthy and with it, a number of ambitious philanthropic initiatives. Recently, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (of Facebook) announced the goal of “curing, preventing, and managing all diseases by the end of the century.” Whilst ambitious, the announcement has drawn attention to the way scientists are joining forces to try and solve huge challenges under the banner of “basic research” which focuses on discovering new scientific insights.

Some of the benefits of targeting basic science research have allowed the development of laser technology, GPS, multi-touch displays and search engines. It also led to the discovery of the first human cancer gene. There are substantial economic benefits too, with the US National Institute of Health estimating that every dollar spent on basic research yields returns ranging from $10 to more than $80. Wealthy philanthropists are increasingly looking at funding basic research alongside governments, and breakthroughs could benefit the standards of living for billions of people across the globe. New discoveries, new industries, new jobs.

Of course, it is difficult to measure in GDP terms the benefits that many technological breakthroughs have – and will – have. GDP is designed to measure things that have been exchanged at some market price and cannot capture the dispersion of ideas, or the increase in knowledge of someone accessing Wikipedia for the first time, or the time and cost savings made in not having to go to a travel agent to book a flight. As products become cheaper (or even free) due to technological innovation, GDP may increasingly mismeasure the progress of the global economy. The gap between what can be measured and our actual experience will widen further (for more on this topic, see our interview with Diane Coyle, author of GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History).

The benefits of the internet, improved global living standards, and potential breakthroughs in basic research should be enough to cure any market participants with Armageddon fatigue. Whilst these developments may not cure market concerns over the limits of monetary policy in the short term, they do suggest that many will continue to prosper long into the future.

One of the prevailing features of the last few years has been the increasing prominence of discussions regarding market liquidity and the seemingly downward trajectory it has taken across fixed income markets. This had led many market participants to question the resulting implications for market stability and volatility.

It makes sense then to try and understand the driving factors behind these trends and the potential pitfalls and opportunities they present for active managers. As someone with experience of attempting to physically transact the various trade ideas and strategies that have been employed, I hope I can lend some insight.

Traditionally, markets are deemed to be liquid when investors are able to transact in them with low cost, little delay and at, or near, the current ‘market price’. Additionally, it is important to note the difference between normal market liquidity, i.e. balanced markets (where there are a roughly even proportion of both buyers and sellers) and stressed markets where the direction of orders is extremely imbalanced.

The extent to which corporate bonds markets are, or ever have been liquid by the above definition is questionable for a number of reasons. Namely, the relatively heterogeneous nature of the asset class makes trading difficult, with issuers having many bonds in existence, with many different characteristics, all being quoted and traded in varying quantities and consistencies. At the same time, the nature and breadth of the investor base is often highly variable, with some varieties of large institutional investors, who may often hold assets for long periods or even to maturity, making up a large proportion of an issue, resulting in lumpy and infrequent trading. This means that matching buyers and sellers at any given time in the market is usually not possible; necessitating the use of intermediaries, namely market makers – in most cases a bank or occasionally a broker. In less widely quoted bonds, this can make liquidity highly dependent on the whims of a select few traders.

Whilst these factors have always been present to a greater or lesser extent, it is fair to say the issue of liquidity and its potential decline are particularly salient now largely due to the combined effects of a period of strong growth in the size of bond markets along with the overarching tendency of the majority of market participants to all be crowding one way or another (i.e. stressed market conditions) as a result of the numerous socio-economic crises and bouts of unprecedented government and central bank intervention which have characterised the post-Lehman period. To a large extent it is the decline in the traditional role of the market maker which has drawn much of the focus, as it has been so marked and in such contrast to the growth in the size of the market.

Despite this, several key liquidity measures, namely average volumes, transaction size and bid-ask spreads all seem to indicate conditions have either recovered or at least stabilised in the years post the 2008 Lehman bankruptcy. Ultimately what this seems to illustrate is that the liquidity risk associated with corporate bond markets has in large part shifted from market makers onto investors, many of whom will, and some of whom may not, be adequately equipped to deal with it. This creates both problems and opportunities for active managers. However in times of normal market conditions, where there is a balance of buyers and sellers, it is clear that liquidity remains robust.

Further, this seems to hold true in other less developed markets also. In the case of UK, statistical evidence provided by the recent FCA occasional paper: ‘Liquidity in the UK corporate bond market: evidence from trade data’ suggests in reference to the post-Lehman period that, ‘there is no evidence that liquidity outcomes have deteriorated in the market, despite the decline in inventory of dealers in this period.’

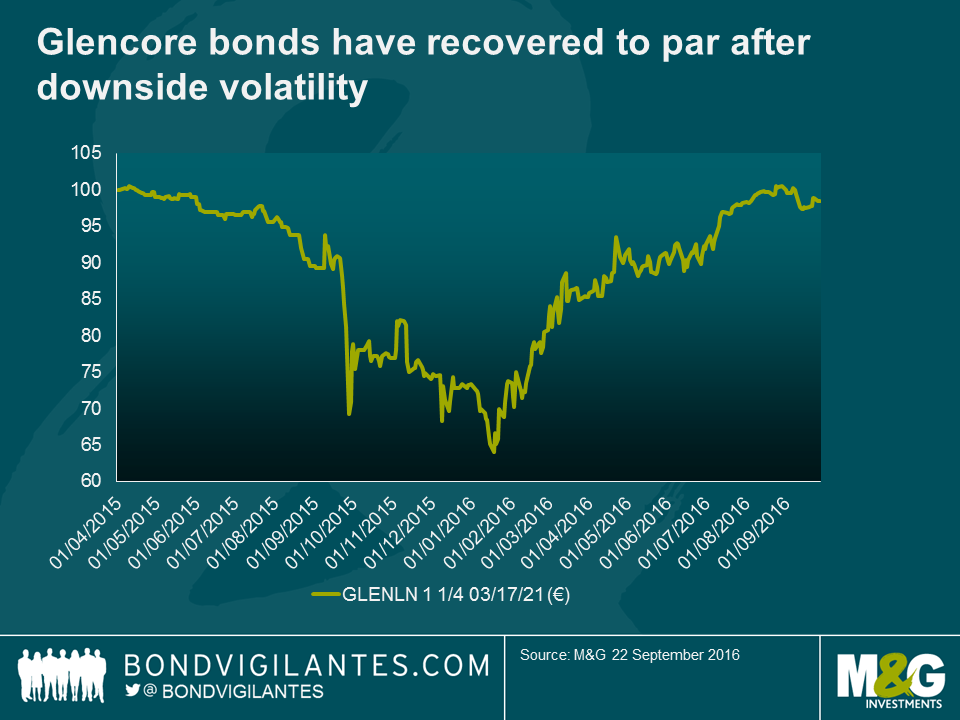

Overall, whilst this may hold true for a number of liquidity measures from a statistical standpoint in normal market conditions, it fair to say that many active market participants would disagree with the premise. The crux of the issue being that the negative effects of the change in liquidity dynamics are only truly apparent when attempting to transact in times of distress, be it for a specific issuer, industry, or the market as a whole. In these instances, there is often a clear weight of negative or positive sentiment resulting in a severe imbalance of buyers and sellers. In an environment where market makers are increasingly reluctant to provide a buffer to dampen price action, clearly volatility can be amplified. In the case of some notable recent examples such as Glencore, bonds have repriced far from any rational fundamental value, dropping in some instances 30-40% in price terms on a limited amount of volume traded before recovering much of that value in subsequent months.

Whilst it can sometimes be frustrating to transact during these periods, they crucially serve to create and highlight significant opportunities for active investors willing to adopt a contrarian view who are able to accept some short term volatility. In these instances, because an investor is in essence providing liquidity to the market, you are able to transact in large size and with a high degree of pricing power, providing a significant advantage from an execution standpoint by allowing you to achieve a price which adequately accounts for the fundamental risks involved, effectively exploiting the inefficiency in market pricing.

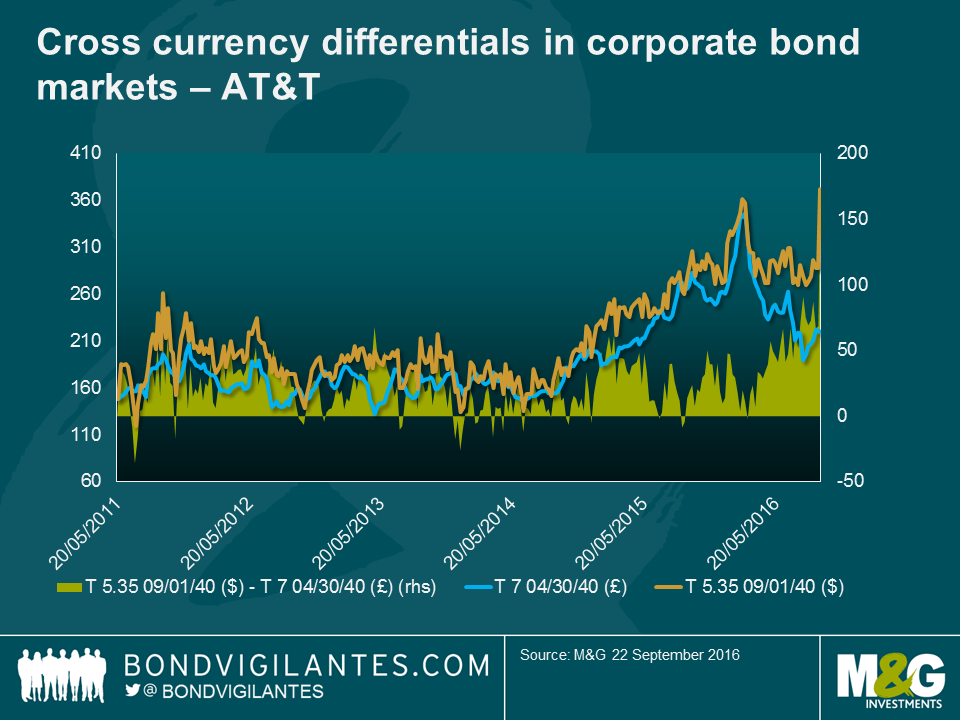

It is fair to say that whilst this is a global phenomenon, it is clear that in less developed markets, namely the UK and to a lesser extent euro corporate bond markets, these effects may be felt more acutely. A large and highly concentrated institutional investor base, combined with this withdrawal in traditional market making by banks, has led to an environment where liquidity can be somewhat transient and fragile. Binary market conditions, due largely to central bank intervention, have led to more frequent and persistent periods of stressed, imbalanced markets. Whilst again this poses challenges day to day from an execution standpoint, the price distortions that result provide significant opportunities in both the domestic markets but most clearly in highlighting relative value opportunities in international debt markets, most notably of late the US. This can clearly be seen in the example of equivalent bonds of the same issuer in different currencies trading at large price discrepancies from one another from time to time before normalising again after a period of reversal potentially allowing an active investor the opportunity to achieve superior returns from essentially the same credit risk by selling one to buy the other and then reversing the trade once the relationship normalises.

A further consequence of these developments has been that trading has become highly concentrated in the most liquid bond issues, often at the expense of the liquidity in those less frequently traded. It follows that bonds that are frequently traded in large volumes are less balance sheet intensive and are therefore more attractive to trade as a market maker. It also follows that an investor who frequently requires liquidity will prefer to trade these liquid securities as they can do so easily and at low cost. The net effect is a crowding of activity in the liquid securities resulting in a sort of bifurcation of liquidity between liquid and illiquid bonds. This leads to increasingly significant price disparities between otherwise comparable bonds, allowing an active investor an opportunity to exploit the inefficiency once again by providing liquidity to the market. This is particularly apparent in the US market where trading is crowded in the most recently issued ‘on the run’ securities whilst the older ‘off the run’ securities are less frequently traded and can often become mispriced.

In all, there are a variety of factors which have contributed to marked changes in the liquidity of corporate bond markets whereby much of the liquidity risk has shifted from traditional market makers to investors, as balance sheets have shrunk and bond markets have grown considerably. Despite this, it is clear that by traditional measures markets remain liquid and function well during normal periods. However it is also clear that this liquidity can be fragile and its absence in times of distress can lead to extreme volatility and excessive mispricing. For an active investor this clearly presents several challenges but more so opportunities, both within and between markets if they are able to withstand short term volatility and manage the risks.

During my free time in August I read the book that has taken the French political and economic landscape by storm (no, it’s not “Capital” by Thomas Piketty). Nobel Prize winning economist, Jean Tirole, has written a book entitled “Économie du Bien Commun” (or “economy for the common good”). The book is written in plain language and attempts to reach a large audience, including readers with very little knowledge of economics. It’s easy to read and through 17 chapters and over 600 pages, Tirole tackles pretty much every issue currently faced by the French economy, from climate change and the European Union challenges to the digital economy.

The most relevant part of the book for me is Tirole’s sharp view of the French labour market. National security and unemployment will be the two key themes of next year’s French Presidential election in May. The former has understandably emerged because of the sizeable terrorist attacks the country has been facing for a couple of years. Unemployment, however, has been a structural issue for 40 years.

Tirole pulls no punches, arguing that France’s historically high unemployment rate is not the result of adverse impacts of the global market economy – a common and handy explanation given by French politicians – but rather a choice that society has made to put in place a very rigid labour market. Conscious that the numbers of unemployed kept rising, the French government decided to create flexible fixed-term contracts (contrats à durée déterminée or CDD) and numerous subsidised jobs instead of adding some degree of flexibility to the ultra-rigid permanent contracts (contrats à durée indéterminée or CDI) and lowering the heavy burden of social security contributions on employees. The numbers are self-evident: in 2013, 85% of jobs created were fixed-term contracts. In addition, 77% of total employment terminations relate to fixed-term contracts.

In reality, a fixed-term contract does not satisfy either employees or employers. Employees are being offered little job protection. Employers are not inclined to renew a fixed-term contract because under French law it is automatically converted into a permanent contract. Therefore, Tirole recommends introducing more flexibility in permanent contracts in order to incentivise French companies to employ more employees on permanent contracts and hence promote “better jobs” over precarious and fixed-term contracts.

Tirole also challenges the current situation in France in which a company laying off an employee must pay termination compensation to the employee but does not bear directly the (rather elevated) cost of unemployment benefits the individual will receive while unemployed and which is funded by the social system. Currently, unemployment benefits are funded through employees’ and employers’ contributions (and also the bond market). Hence, when a company decides to lay off an employee, it is both detrimental to the employee (financially, psychologically, socially) and the social system. Tirole therefore introduces the same concept as “polluter pays” with job lay-offs by making a company not only pay the employee’s termination compensation but also contribute to the cost of unemployment benefits paid by the social system to the individual whilst unemployed. He adds that the measure would be tax neutral for companies as a whole because the penalty would be offset by bonuses for other companies (through reduced social security contributions).

Finally, Tirole acknowledges that it is not an economist’s duty to determine whether people should work 35, 18 or 45 hours per week. Nevertheless, he also fiercely sweeps aside the argument that the reduction of working time will create more jobs (describing it as a “false solution” that has no theoretical nor empirical backing). There is no doubt that opponents to one of the main French labour unions contemplating a weekly working time of 32 hours (from 35) will quote Tirole.

I am hoping that the 2014 Nobel Prize winner’s authority on economics may provide food for thought to the French Presidential candidates. In the past, Thomas Piketty served as advisor to the Socialist Party candidate Ségolène Royal during the 2007 French Presidential campaign. His idea of a simplified tax system was interesting and much needed. However, Mrs Royal lost her Presidential bid against Nicolas Sarkozy and since then no simplification of the tax system has been implemented. Let’s hope that Jean Tirole’s common sense with regards to the labour market wins the ears of the next French President. This may be beneficial for the common good.

For fixed income fund managers it was once the case that if you understood the evolution of the relative sizes of the various cohorts of the young, the working, and the retired in a population, you could predict bond returns. Lots of workers relative to the “unproductive” young or elderly meant low wage pressures, lots of demand for savings assets such as bonds, and lower government borrowing. When workers became scarce, wages would rise, inflation would increase too, and bonds would sell off. The demographically based bond models worked a treat in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. But sometime around 2005 there was a complete breakdown in the relationship between bond yields and demographics. Based on the model alone we’d expect double digit long dated gilt and US Treasury yields, rather than the 1.6% and 2.4% we have today.

In this, the latest in our series of Panoramic publications, I look at the old demographic fixed income models and examine why they used to work, and why they’ve been rendered useless by globalisation.

Please click here for the M&G Panoramic Outlook web page.

When investors buy or sell financial assets they try to analyse likely outcomes. This basically revolves around three main issues.

- What is the capital upside?

- What is the capital downside?

- What income is earned from the security?

The dramatic fall in bond yields means that this traditional approach to investing will have to be examined.

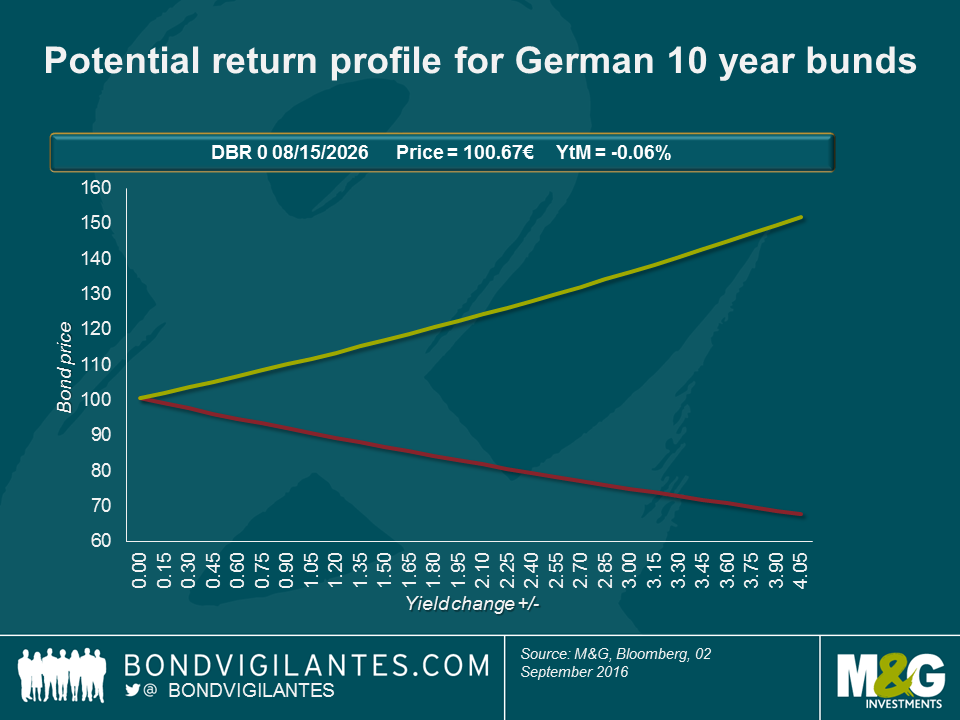

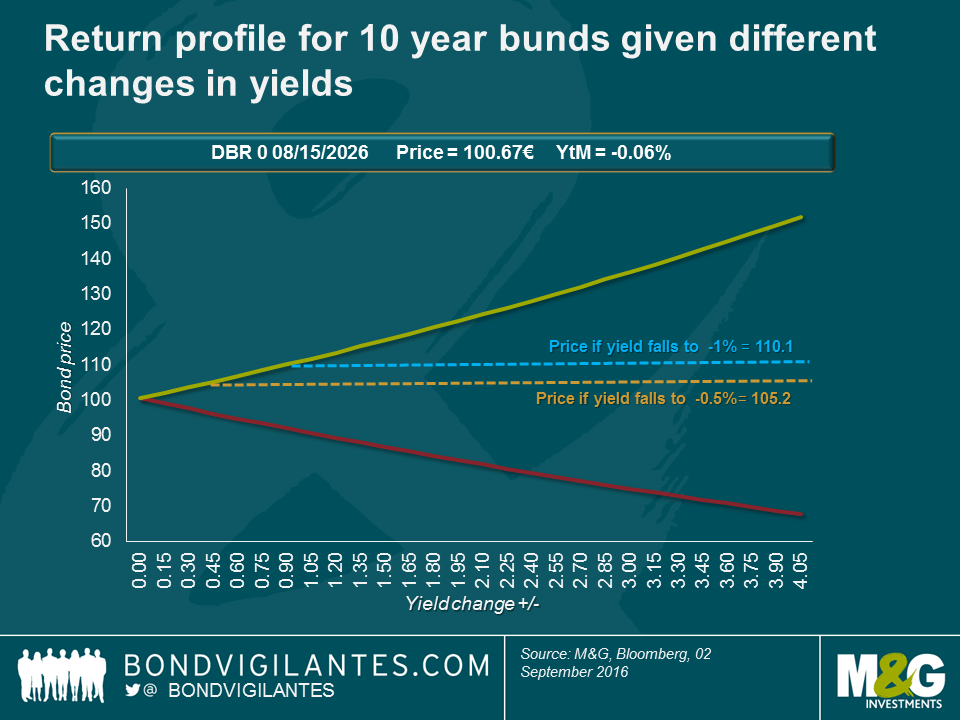

One way to do this is to model real world outcomes. Below is a depiction of how the German bund 0 percent 2026 will move in price given different yield scenarios. Assuming the current yield is zero the price is 100, if interest rates were to fall -4 percent the price of the bond will increase to 151.9 , and if rates were to rise by 4 percent the price will to fall 67.8. It is possible to plot the theoretical capital upside and downside, and given that it is a zero coupon security it will earn the investor no income over its life.

The above approach is the traditional way an investor would analyse a bond, however one has to remember that investors can think of cash as a strong bond alternative. When holding physical cash, the investor knows the capital upside and downside are both zero, and the income returned by physical cash is zero. Cash is the ultimate low volatility security, but earns the investor no income.

This lack of income has given bonds an historical edge over physical cash. Investors were happy to take extra income and potential capital gains and losses in bonds versus cash. Developed bond markets are now at the point where the income on a 10 year bund and a 100 euro note is exactly the same (zero) and the yield advantage of owning a 10 year bund is gone. However, the potential capital gains and losses of owning a bund still exist. Consequently, at these low yields I believe the upside for bunds versus cash is limited.

When faced with a greater return and less volatility why would investors buy a negative yielding bond rather than hold cash? One advantage government bonds have over cash is safety, they are harder to lose, steal, and be destroyed. And there is a greater cost in holding cash due to its physical nature. This risk can be removed via secure storage, traditionally in a vault. This means that a holder of cash would become indifferent when the costs of holding cash is the same as the negative yield earned on bonds. If we assume this is around 1 percent, then the below graph illustrates that investors would be willing to hold a bond yielding less than zero to maturity even with the potential risks to capital.

Markets are dynamic, and if this negative yield environment persists, market structures will probably evolve to potentially provide more interesting ways to store cash. One solution would be for a bank to issue an ETF based on negative yielding cash, akin to other physical ETFs. As opposed to commodity or equity backing, the ETF would have cash stored safely at a variety of locations, where security would be strong and access would be hard to achieve. The ETF provider could then charge the client a fee (say 1 percent per annum) for depositing the cash, incur low costs of storage of let’s say 0.5 percent, and earn 50 basis points of return. Such an ETF would allow both small and large transactions, and allow customers from individuals to institutions to store their money efficiently at a zero rate before fees.

In theory, the upside in bonds is limited by the physical alternative of cash. Therefore the risk reward of owning bonds is skewed. Below the zero line the upside is limited, while the downside still has the ability to hurt.

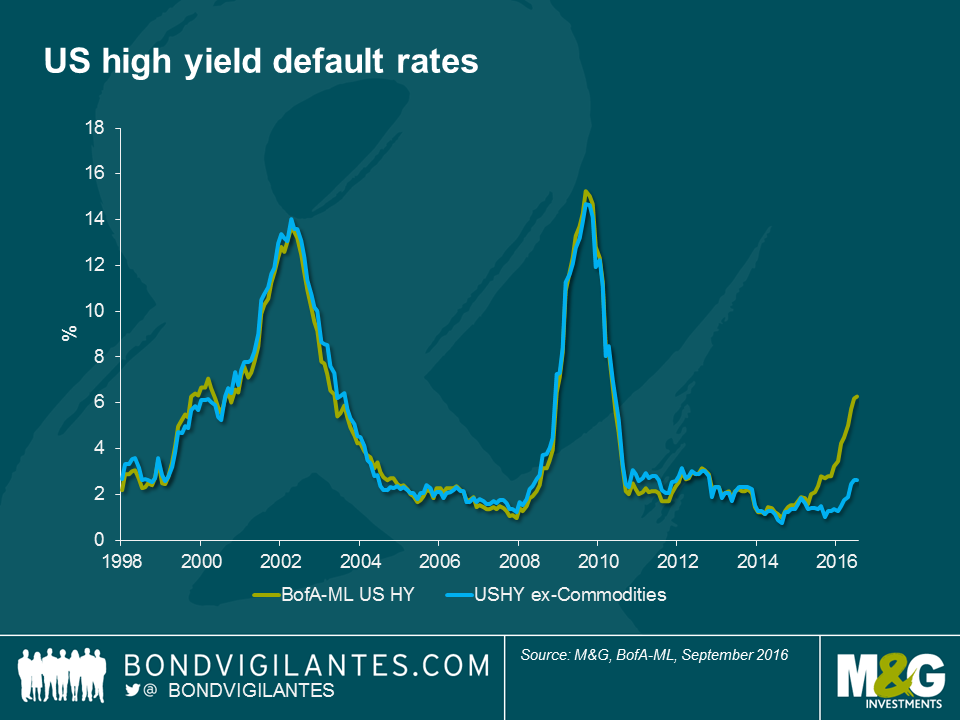

In order to assess value in credit markets, bond investors usually make some assumption about the future path of corporate default rates. This assumption generally stems from macroeconomic forecasts (strong/weak growth = low/high defaults rates) or sector specific events (like oil price movements). Following this, it is possible to get an indication of whether investors are being over- or undercompensated for investing in corporate bonds by assessing the level of credit spreads.

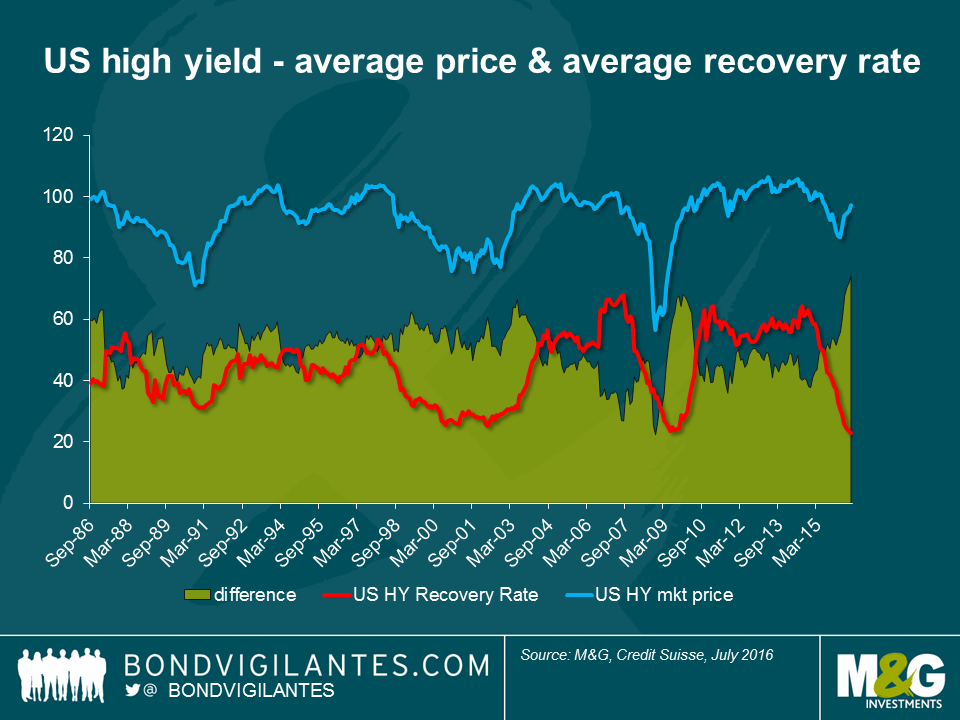

If this seems like a simplistic approach, it is. Default rates don’t give the full picture. It is important to add more information to the valuation assessment; specifically, in the event of a default how much money will investors get back? This is an increasingly important piece of information in a world where low interest rates and unconventional monetary policy has helped push high yield corporate bond prices back towards all-time high levels despite late cycle risks. Sometimes, it might be worth buying a default candidate if the level of recovery compensates for the cost of entry and the headache involved.

Over the past year and a half, US high yield recovery rates have plunged from 61% in December 2014 to a record low of only 23%. Because of the fall in recovery rates, the difference between the US high yield market price and recovery rates is at an all-time wide level. Those US high yield investors that own a bond when it defaults are now losing more money on average than ever before.

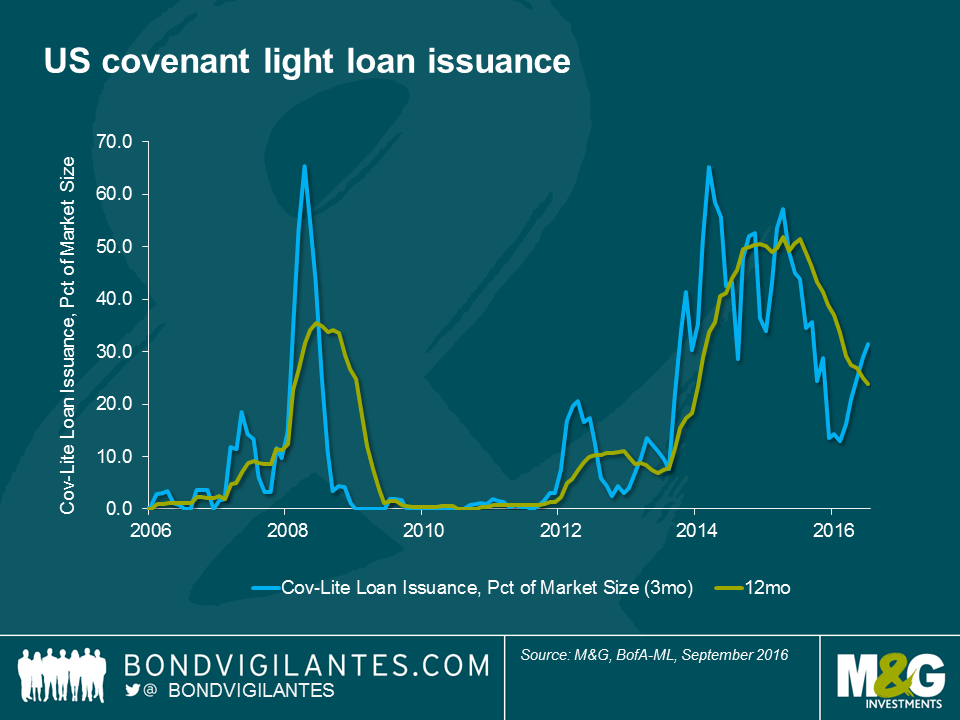

We think that there are a couple of reasons for the fall in recovery rates. Firstly, markets tend to leave investors as price takers for fear of missing the returns that other market participants are enjoying. In their quest to ‘stay invested’, bond holders will typically forgo covenant protections that will impact ultimate recoveries. One of the proxies that we pay attention to, given the close correlation to issuance standards in the high yield market, is the share of covenant lite issuance in the leverage loan market. The period of 2012 to 2015 saw a massive increase in covenant light loan issuance. This means that lenders have much weaker protection in the form of incurrence covenants rather than maintenance tests. The US high yield energy market is a case in point. Underpinned by $100 oil price, high yield investors paid far too little attention to bond documentation, leaving significant room for creditors to be “primed” (the act of granting a new lender higher claims priority over an existing creditor).

We think that there are a couple of reasons for the fall in recovery rates. Firstly, markets tend to leave investors as price takers for fear of missing the returns that other market participants are enjoying. In their quest to ‘stay invested’, bond holders will typically forgo covenant protections that will impact ultimate recoveries. One of the proxies that we pay attention to, given the close correlation to issuance standards in the high yield market, is the share of covenant lite issuance in the leverage loan market. The period of 2012 to 2015 saw a massive increase in covenant light loan issuance. This means that lenders have much weaker protection in the form of incurrence covenants rather than maintenance tests. The US high yield energy market is a case in point. Underpinned by $100 oil price, high yield investors paid far too little attention to bond documentation, leaving significant room for creditors to be “primed” (the act of granting a new lender higher claims priority over an existing creditor).

Secondly, an intended consequence of quantitative easing policies is the portfolio rebalancing effect, where investors increasingly turn to riskier assets in order to generate positive returns. One of the unintended consequences of this is the resulting misallocation of capital. Companies operating in an economic regime of quantitative easing take much longer to fail, as evidenced by the very low default rate of the last decade (with exception of the 2008 financial crisis period). In this environment, companies are incentivised to issue debt at unusually low yields, and are encouraged to allow cash to leak from the business in the form of distributions to shareholders and coupon payments to creditors. When the unfortunate time comes to wind up the business, creditors find that there is less cash to go around and more indebtedness, resulting in the low recovery rates we see today.

With recovery rates falling and default rates likely to rise from current low levels, those looking to get access high yield markets are going to have to “mind the gap” that has opened up between recovery and default rates. In an environment devoid of yield the attraction to chase income is only too understandable. Yet the risks are increasingly apparent and investors in high yield should consider their downside as well as the potential upside.